The real Mother’s Day present is ending forced family separation – says working Filipino mothers who labor as domestic workers in the US while their children are in the Philippines.

Image courtesy of Damayan Migrant Workers Association

Image courtesy of Damayan Migrant Workers Association

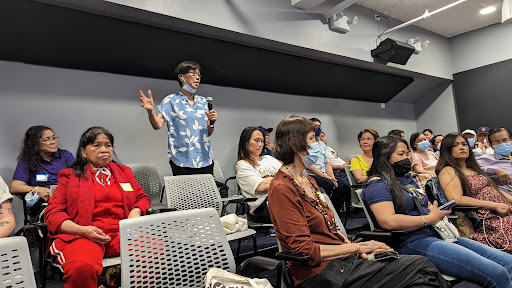

It was the day before Mother’s Day at the People’s Forum in Manhattan. Fifty, mostly women, migrant workers from the Philippines gathered in the basement theater for a premiere of the documentary “MaiMai.” The film, like this Mother’s Day event, demonstrated how globalized capitalism has strained migrant motherhood.

“This gathering is to recognize the mothers forcibly separated from their children,” announced the facilitator in Tagalog. “Who has their kid in the US?” Solemnly, one mother raised her hand. “Whose children are in the Philippines?” The remaining mothers in the room raised their hands in unison.

Most of the women are above 30 and labor as domestic workers in New York to send money back home to the Philippines. MaiMai, a nickname for Mary Claire Cahumnas, is one of these women. Unlike the others, she was joined by her six children at the event. The young ones sat together in the corner, tossing in their seats, joking with each other as they anxiously waited for the film, starring their life story, to begin.

“MaiMai” is the latest installment of the Damayan Migrant Workers Association’s Baklas Film Series. Directed by Filipino filmmaker Mike Cabardo, it follows the 44 year old domestic worker trafficking survivor and her children as they reckon with being reunified after seven years of separation.

MaiMai is one of the 1.1 million women who work overseas to send remittances to family in the Philippines (Philippine Statistics Authority, 2022).The country depends on workers’ remittances for almost one tenth of their GDP (World Bank Group, 2023). Labor migration became a government policy beginning in the 1970s and today roughly one tenth of the population lives abroad (O Neil, 2004; Maruja, 2017). Since the 1990s women have outnumbered men as overseas foreign workers in land-based employment. The top occupation for women is domestic work (Maruja, 2017). Shaped by government policy, motherhood for many in the Philippines has become associated with forced migration, family separation and all too often, labor trafficking.

MaiMai’s life is testament to the cost of the Philippines government policy. Through the lens of her life, the film discusses the root causes of family separation and labor trafficking and its traumatic impact on the family. By showcasing how the Cahumnas family is trying to heal from trauma, the gathering aimed to inspire the mothers in the room to confront the mental health and family strain caused by separation and work as a community to heal.

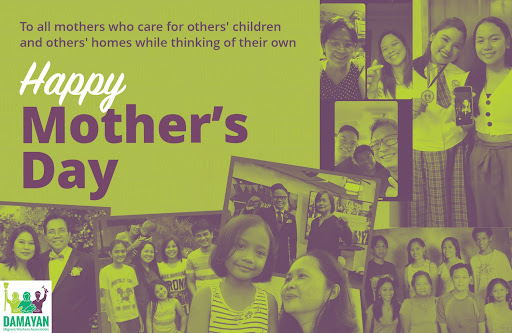

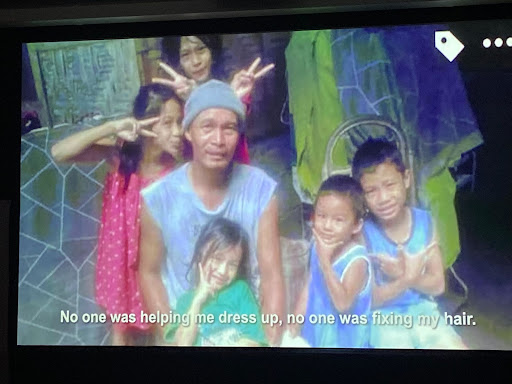

This frame of the documentary shows two of MaiMai’s children comforting her during an interview

This frame of the documentary shows two of MaiMai’s children comforting her during an interview

The film begins with MaiMai on the streets of New York commuting to her housekeeping job. She recounts her story that began more than a decade earlier. When her children were under the age of ten, the youngest being six months old, she put them to bed one night before slipping out to the airport. She headed to the US to work as a domestic worker for an American family. Once she arrived her employer did not pay her what was promised and often prohibited her from leaving the house.

Over the next seven years she labored under these conditions and her husband at the time utilized her remittances to take care of the children. For a period of time she could not send money home because her traffickers withheld her pay.

This frame shows five of MaiMai’s six children with their father in the Philippines in the 2010s

This frame shows five of MaiMai’s six children with their father in the Philippines in the 2010s

“I had a lot of fear because I was undocumented before. My family didn’t know. I hid it from them,” shared MaiMai on the post screening panel.

With the help of Damayan, she earned a T- visa, colloquially referred to as a trafficking visa, which provided her legal stay and passage for her children to come to the US. However, once they were reunited, their problems did not end.

“I have been reunited with my children for four years now. But I still work seven days a week and it’s very painful,” shared Mai Mai through tears.

MaiMai’s remark speaks to the precarity of domestic work in globalized capitalism. Her eldest daughter Yanna Cahumnas shared, “Here in the US we have a mother but we still don’t feel it because she is still working seven days a week. We don’t have time to bond.”

“My siblings have anxiety and trauma. My siblings don’t have memories of my mother because they were babies when she left. So we are growing up on our own.”

Photo courtesy of Damayan Migrant Workers Association

Photo courtesy of Damayan Migrant Workers Association

Left to right: MaiMai Cahumnas and Yanna Cahumnas

The Cahumnas story demonstrates the cost of migrant motherhood. To discuss the roots of and solutions to forced migration, separation and labor mentioned in the film, a panel of survivors, organizers and allies gathered. On the panel, MaiMai was joined by her eldest daughter and Damayan Intern, Yanna, the filmmaker, Mike Cabardo, the Medical Director of Homeless Services at the Family Health Institute, Dr. Victor St. Ana and Co-Director of the Barnard Center For Research on Women and scholar on domestic workers history, Premilla Nadasen.

Left to right: Riya Ortiz, MaiMai Cahumnas, Yanna Cahumnas, Dr. Vic St. Ana, Professor Premilla Nadasen

Left to right: Riya Ortiz, MaiMai Cahumnas, Yanna Cahumnas, Dr. Vic St. Ana, Professor Premilla Nadasen

Mental Health and Migrant Motherhood

Riya Ortiz, executive director of Damayan, facilitated the panel discussion and asked the first question in the spirit of mental health awareness month, “How does forced migration and the resulting family separation continue to affect your family? Did that affect your mental health?”

MaiMai answered first. “We are going through family counseling but I have to keep working to pay for the rent, bills, clothes and food. I still take an additional part time job and get home at 11 or midnight. Because I will do everything for my children but I am not sure if they understand. One child wants to go back to the Philippines. So I keep asking them what I should do?”

All the while, daughter Yanna held her head, heavy with tears, in her hands. With some support and encouragement from Ortiz, Yanna gathered strength to respond. “When Nanay [mother] left I was in kindergarten. She didn’t say goodbye. She put us in bed to sleep then left because she was afraid she would not be able to leave if we were upset. I remember there were meetings in school but my mother wasn’t there. I understand but it still hurts.” She began to cry again. The panel paused to give her space. Then the audience cheered her on in support.

“We are trying to heal in therapy. My mother talks about her guilt, why she left us. But we need time to heal. I am thankful for my mother for pushing us to go to therapy. We hope we will not be strangers anymore. To the mothers in the crowd, please do not be afraid to ask for help. If you need therapy, Damayan can refer you to someone.” The crowd erupted in applause yet again.

Three of MaiMai’s children in their home in Queens, New York

Three of MaiMai’s children in their home in Queens, New York

MaiMai and Yanna’s experience speaks to the larger experience that Dr. St. Ana witnesses as a pro bono physician for labor trafficking survivors and uninsured workers, “The experience of forced migration and separation can lead to that feeling of being destabilized. That in turn can turn into depression and anxiety.”

Migrant mothers can also develop mental health challenges apart from the family if they are labor trafficked. Dr. St. Ana witnesses C-PTSD in his patients who are trafficking survivors.

Migrant Mothers Labor Trafficked To Take Care of Other People’s Children

“I was a live-in worker. It meant anytime they could wake me up. When I was sleeping they would wake me up to get milk for the baby or get them water. I was afraid because I did not have papers. They didn’t have to wake me up to get the milk because they can do that for the baby or get themselves water. On the contract it said 7am-7pm but they were not following it.”

MaiMai’s experience exemplified the three elements of trafficking that are hidden in plain sight. Her employers forced her to submit to exploitative work by restricting her movement (force), not following the contract and withholding pay (fraud) and utilizing her lack of documentation as a fear tactic (coercion).

MaiMai’s circumstance exemplified the most vulnerable to labor trafficking, foreign nationals with or without documentation who live with their employer. Employers exploit foreign nationals by threatening deportation and confiscating documentation. Those whose visas are tied to their employer are especially vulnerable because if they leave the abusive situation, they become undocumented (National Human Trafficking Hotline, 2023).

Healing as a Community of Isolated Mothers

While forced migration, separation and exploitation is a widespread experience for Filipino families, the community is keen on healing.

“How do we begin to heal? Having community and building connections is an incredibly important part of the healing process,” shared Dr. St. Ana. “A major symptom of depression is withdrawal. Withdrawal from communities and people you love.” Not only is community the antidote to social isolation but also to self-awareness. “By having a community it is easier to build insight into one’s own condition. To see that what they are experiencing is not so unique just to them. You see the commonalities and experiences and you don’t feel so alone.”

While healing can look very different for each person, Dr. St Ana affirmed that community is the biggest and most enduring medicine. “That’s what Damayan does,” he concluded.

Yanna experiences the benefit of community firsthand, “Damayan is like a second home to me. I don’t have a mentor in my family. But I have Tita [aunt] Riya who is my Nanay [mother] in Damayan. We share stories and give advice. There’s Moira who I share my trauma with.”

Dr. St. Ana expanded on Yanna’s encouragement by sharing, “The hope is that with your new life here you can create new memories that are positive. Through those experiences you can reframe what you have all been through. I see that as potential ways to heal. Hopefully together we can continue to talk about this openly as we have today so we don’t feel ashamed. That there is no more stigma against having experienced these things because it’s all natural reactions that many people here have been through.”

Damayan staff, worker leaders and members posing for a photo during a Filipino lunch

Damayan staff, worker leaders and members posing for a photo during a Filipino lunch

Forced Family Separation Embedded in the Economy

While these reactions to family separation are normal, the panel concluded that the migration, separation and exploitation experienced by Filipino women should not be normalized.

“It’s really unfair that some families of the working class and working poor have to decide between do I spend time with my children but we are hungry or do I leave the Philippines, work abroad and give them a better life but we’re not together?” lamented Ortiz.

In Damayan’s analysis, the economic conditions that necessitate migration from the Philippines were formed by US imperialism and the corrupt Philippine government formed in the wake of US colonialism to serve the United States’ interests. Damayan envisions a future where Filipino families find sufficient employment and livelihood in the Philippines so no family will be separated again.

Exploitation of Domestic Workers Embedded in Capitalism

In the meanwhile, Damayan is actively trying to improve the conditions of the domestic workers who do have to migrate to survive. Once domestic workers get to the US, they are met by a society that demands but also devalues domestic work (Fraser, 2016). The devaluation is embedded in financialized capitalist society, argues sociologist Nancy Fraser (2016) in “Contradictions of Capital and Care.” Before the second half of the 20th century, women in the family of middle class America were responsible for cooking, cleaning, child-care and elder care without pay. Resultantly, the work was cast as women’s work. This work, which sociologically speaking is referred to as social reproduction, has historically been remunerated with virtue and love, while work outside the home, economic production, has been compensated with money (Fraser, 2016). In the 1970s middle and upper class women began to escape this subordination as economic conditions necessitated two income earner households. However, the gutting of public welfare exacerbated a gap of who will take on the reproductive responsibilities of maintaining the household and caring for family members? Middle class families turned to privatized care in which low-wage workers filled the gap (Nadasen, 2021; Fraser, 2016).

Filipino domestic workers enter this labor market under the social conditions that exploit domestic workers. Today, the majority of domestic workers are immigrants and women of color. However, even though these workers are provided cash wages, they are not treated like any other worker in the sense of protection from discrimination and benefits.

“Domestic workers are excluded from key labor laws,” shared Nadasen. They are excluded from the federal National Labor Relations Act among others that provide protection against discrimination, provide minimum wage, overtime pay, safe work environments and the right to bargain collectively.

As a result, domestic workers cannot survive on a 40 hour work week. Even the luckiest, like MaiMai, who is eligible for certain government benefits on her T-visa, continue to work seven days a week until late at night to afford rent, bills, clothes and food for her children (US Office of Refugee Resettlement, 2023). As her daughter previously expressed, in the US Yanna feels like a stranger to her mother because she still works seven days a week so they do not have time to bond.

Instead of caring for her children, MaiMai is forced to “care” for someone else’s children. The exploitation of domestic workers is propagated by the narrative that domestic workers do this work because they care for the employer.

“Employers sometimes refer to domestic workers as care workers. They say that domestic workers might be part of the family. They might assume that you love their children. That you care for their children. What they actually do is that they use that language of love and care to ask you to stay late, work longer hours, and take less pay. To sacrifice your own life and your children for their families and their children,” explained Nadasen.

MaiMai resonates with this because when was trafficked as a live-in housekeeper, “My trafficker called me part of the family.”

Comparatively, Nadasen noted, “But what I have seen here today – that is care. That is love. When I see children talking about the sadness and the trauma they experienced being separated from their parents, or seeing the parents feeling the pain from separation. That is what care is.”

Photo courtesy of Damayan Migrant Workers Association

Photo courtesy of Damayan Migrant Workers Association

Premilla Nadasen speaking on the post screening panel

A Future Without Family Separation

Ortiz is also a victim of forced family separation herself. “When I was eight my mother left for the US for the same reason. People ask, is it a fair exchange to be able to go to a good school and become comfortable because my mother is abroad? It’s unfair to get asked this question.”

“The employers of domestic workers in the US, mostly rich and white, will never have to be confronted with that question. You miss birthdays, Christmas, weddings, graduations, even illnesses and deaths. That’s out of the question for them but for us it’s a given.”

As Damayan members’ experiences prove, depression, anxiety, strained family relationships and exploitation are the givens of migrant motherhood.

“Most of all, the way the situation works now where people have to be forcibly separated from their children is not one that should exist. It should not exist for anyone,” stated Professor Nadasen. The crowd cheered in agreement.

Nadasen shared how this vision can be realized, “The other part about this that’s important about the community is that you come together to make a change. You come together to organize and to empower people so that this does not continue to happen so that we can begin to change laws. Sharing stories is part of a process of healing, part of a process of educating. There are people who don’t know or understand what’s happening. By sharing the stories you are beginning a process of change.”

Emboldened by sharing her story with the community, Yanna is determined to improve the experience of the next generation of reunited Filipino families. “Now we [Damayan] are focusing on the children of Damayan members. Damayan is here so if you have children or children arriving here we can help enroll them in school. Text me or call me. I am here to help.” After high school graduation this month she will join Damayan full time. “I am shadowing Riya and Lydia to become a leader of the next generation at Damayan. It makes sense because my Mom is a labor trafficking survivor.”

Ortiz expanded on their plans. “Yanna and I are talking about doing an orientation with the children in the Philippines before they get reunited in the US. They don’t know that their mother will be working seven days a week and they will be mostly living alone. We want to know their hopes and dreams so when they come here we can support them properly. Even if the kids earn their own money, go to college, it is not enough. There will always be a hole unless you address the trauma from family separation and forced migration. Those things don’t go away, you just learn how to manage and you keep recovering and keep persisting.”

Ortiz concluded the panel by recognizing MaiMai’s progress amid struggle. “This is not a story of failure or defeat. The survivors always persist. Ate [older sister] Mai, you are setting a very good example to your children by going to therapy. They may not understand it now. But in the future they will appreciate it.”

Community Healing at Work

The Q&A following the panel transformed the basement into a townhall of mothers sharing their similar experiences and exchanging ideas.

“What Ate MaiMai did, I did it, too,” shared one Damayan member. “When she left her children after putting them to sleep is what I did too. Now my heart is pounding. It was better for me to see them sleeping than seeing them while they were crying. Maybe I would not step on a plane! I feel sorry because I feel like a selfish mom. We cannot undo what happened but if we could do it differently how would you like it to be done?”

Another member and trafficking survivor shared with the room. “It’s important to have constant communication with your children and leave them with the right person.” Discussion continued along the lines of children’s culture shock in the US, their mental health challenges when experiencing parental separation and suggestions of what should be done while children are in the Philippines.

Photo courtesy of Damayan Migrant Workers Association

Photo courtesy of Damayan Migrant Workers Association

Damayan member participates in the Q&A

Damayan concluded the event with a celebratory cake and distributed a token of appreciation to every mother in the room. However, the takeaway message is clear: the real Mother’s Day present for the Filipino community is ending forced family separation and replacing it with livelihoods in the Philippines to enable them to take care of their children.

Damayan members who are mothers cut cake and receive a Mother’s Day gift from Damayan

Damayan members who are mothers cut cake and receive a Mother’s Day gift from Damayan

MaiMai’s film will be published online soon. Follow Damayan’s Facebook page to be notified when it is released.

Remarks by MaiMai and Yanna were delivered in Tagalog and immediately translated by Ortiz to the crowd.

Joanne Dolman provided a personal live translation of the speeches, remarks, questions and answers to me throughout the event.

Jules Grifferty (they/them) is an MA in Labor Studies at the CUNY School of Labor and Urban studies.

References

Asis, Maruja M.B. (2017). The Philippines: Beyond Labor Migration, Toward Development and (Possibly) Return. The Migration Policy Institute. https://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/philippines-beyond-labor-migration-toward-development-and-possibly-return

Damayan Migrant Workers Association (2023). 34th Family Reunited on US Soil. https://www.damayanmigrants.org/news3/2023/2/23/family-reunification-grace-aranjuez

Damayan Migrant Workers Association. (2023) Honoring Filipino Mothers with Damayan Baklas Film Series: “MaiMai”. https://www.damayanmigrants.org/news3/2023/5/18/honoring-filipino-mothers-with-damayan-baklas-film-series-maimai

Fraser, N. (2016). Contradictions of Capital and Care. New Left Review, 100, 99-117. https://newleftreview.org/issues/ii100/articles/nancy-fraser-contradictions-of-capital-and-care

Office of Refugee Resettlement, an Office of the Administration for Children & Families within the US Department of Health & Human Services. (2023). Fact Sheet “Victim Assistance”. Washington, DC. https://www.acf.hhs.gov/orr/fact-sheet/fact-sheet-victim-assistance-english

O Neil, K. (2004). Labor Export as Government Policy: The Case of the Philippines. The Migration Policy Institute. https://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/labor-export-government-policy-case-philippines

Nadasen, P. (2021, July 16). How Capitalism Invented the Care Economy. The Nation. https://www.thenation.com/article/society/care-workers-emotional-labor/

National Human Trafficking Hotline. (2023). Domestic Work. https://humantraffickinghotline.org/en/labor-trafficking-venuesindustries/domestic-work

Philippine Statistics Authority. (2022). 2021 Overseas Filipino Workers (Final Results). https://psa.gov.ph/statistics/survey/labor-and-employment/survey-overseas-filipinos#:~:text=The%20number%20of%20Overseas%20Filipinos,1.77%20million%20estimate%20in%202020.

World Bank Group. (2023). Personal Remittances received % of GDP Philippines. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/BX.TRF.PWKR.DT.GD.ZS?locations=PH