By Abbie Harper

The paradox of noble-cause corruption, unethical actions taken in pursuit of the greater good, is so prevalent in the non-profit sector that it’s become normalized. And due to the United States government’s ongoing divestment in public health, we have no choice but to rely on these organizations to access social services and support. But what kind of “support” repeatedly results in systemic violence being inflicted on marginalized individuals and communities? And what kind of “support” industry fails to support its workers? Every larger system is responsible to the people who make it work, as well as to the people it serves. Both direct service delivery and efforts at larger social change are undermined in an eroding environment that fails to support its workers.

When I saw a class on worker cooperatives and the solidarity economy was being offered in my community, I signed up. I wanted to find out if there was a way to build a better, more ethical organization to serve the complex mental health needs of a society. That’s what I was hoping for. And that’s precisely what happened. But first, I want to tell you how I got here.

Shortly after beginning my job on the National Eating Disorders Association (NEDA) Helpline, I became acutely aware that without adequate staffing, additional training, organizational inclusion, and a psychologically safe work environment, a job I genuinely loved would eventually become unsustainable. I was also operating under the false assumption that a mental health non-profit would embrace the idea of prioritizing the mental health of its frontline workers.

When my co-workers and I unionized for a psychologically safe and sustainable workplace, NEDA leadership was so threatened by our collective strength that they fired us and attempted to replace our humanity with an inept AI chatbot. The chatbot’s spectacular failure and immediate shutdown made global headlines and caused overwhelming damage to their reputation, but it wasn’t enough to stop NEDA from shuttering the Helpline forever. The truth is NEDA was well aware of their Helpline worker exploitation, burnout, and turnover – they relied on it to uphold their delicately maintained organizational power structure.

A visit to Glass Door makes it clear that NEDA’s brand of employee exploitation is pervasive within the many non-profit organizations that provide direct mental health support. And like NEDA, these organizations insist the answer to expanding access to mental health support is to invest in AI instead of the human workers on the front lines.

My experience at NEDA turned me into both an organizer and a bit of a professional troublemaker. As I collected my severance, I wondered what it might look like to create a new Helpline from the ground up. In labor organizing, oppressive hierarchical power dynamics are often subverted by doing the opposite of what “the boss” would do. NEDA is far from the only non-profit insisting the answer to expanding access to mental healthcare is to partner with big tech, rather than partner with the communities they claim to serve. But what if we could fill the gap in the workforce with peer support workers instead? And what might it look like if worker cooperatives provided public services instead of nonprofits?

Signing up for Worker Cooperatives 101 would be one of the most profound decisions I have ever made. It reinforced my belief that it was possible to both be ethical and make significant systemic change; you just need creativity, tenacity, integrity, and most importantly, community. Unlike the top-down approach of a CEO and Board dictating directives, worker cooperatives foster a sense of shared ownership and responsibility for the workplace environment and its often far-reaching outcomes. And after all, social movements almost always start from the bottom up by reminding people that in a broken system, solidarity is our greatest tool for change.

I can’t think of a more direct challenge to “the boss” than worker cooperatives and the solidarity economy. My teachers and classmates have only strengthened both my belief that big problems will require big solutions and my belief in myself. Perhaps the solution I’ve been searching for is me.

PS: And now, Abbie Harper is a new student at SLU, in our graduate certificate program WDCO

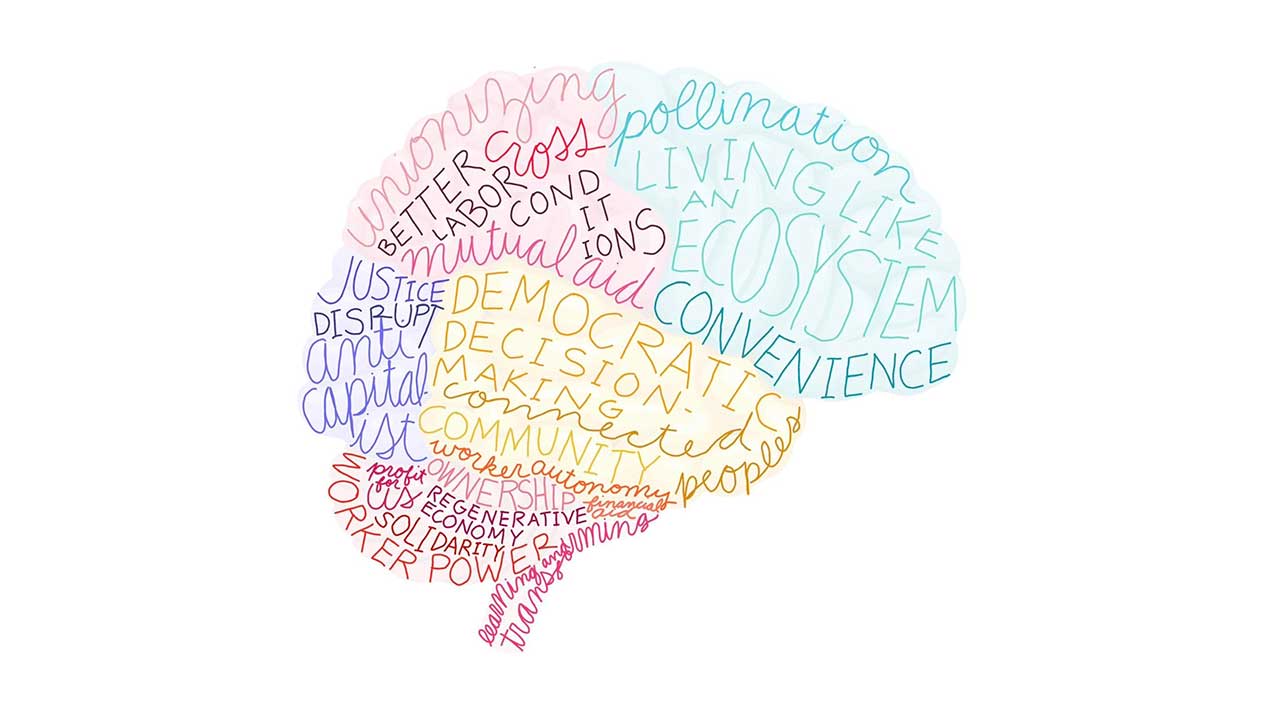

See class activity of why co-ops matter taken from a menti to a brain trust: