Featured photo via Urban Upbound

By Paula Bonfatti

For the past three months, I have interned in the research department of Urban Upbound, a nonprofit organization that provides services to public housing residents in Queens, New York. Urban Upbound supplies this community with tools and resources needed to achieve economic mobility and self-sufficiency; their vision is to help residents break cycles of poverty. They primarily serve the Queensbridge Housing Development, which — with its 3,142 apartments — is known as America’s largest operating public housing project.

In New York City, there are over 607,000 people living in public housing developments under the New York City Housing Authority (NYCHA). 110,000 (18.1%) of these residents are children under 18 years old. Historically, public housing developments have been criticized by the mainstream as isolated, low-income urban population. Some critics contend that this housing creates vertical structural poverty in socioeconomically depressed neighborhoods. In addition, critics charge that these concentrated pockets of poverty are subject to high crime rates, unemployment and low turnover. However, NYCHA has 328 public housing units throughout the City’s five boroughs and serves 175,747 families, and has committed itself to playing an important role in fighting urban poverty and leveraging economically vulnerable communities.

NYCHA residents have been the subject of many discourses led by New Yorkers, urban sociologists, the media, and administrative and political institutions. People living in public housing are the objects — or victims — of these varied discourses, resulting in the saturation and limitation of meanings around themselves and around public housing, and perpetuating the dominant, stigmatized social imaginary. It is possible to identify, within the many discourses about public housing, recurrent meanings attributed to NYCHA housing (or, “the projects”) and its residents: ones of violence, drug abuse, disturbance of the peace, and “anti-social” behavior. This results in the stigmatization and homogenization of economically vulnerable families.

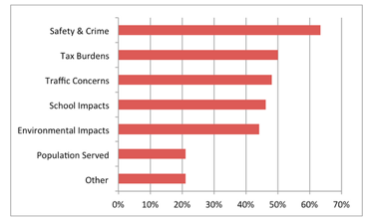

Research evaluating community opposition to affordable housing development projects, conducted in 2014 with 75 developers from New York State, shows the most commonly reported reasons for opposition faced by developers, when trying to build affordable housing. The results show irrational fears and reveal the prejudiced and stigmatized social imaginary around affordable housing.

The research also points that one out of every five developers indicated opposition to the people the developments are expected to serve. The terms used to refer to affordable housing residents include: “those people”, “welfare recipients”, “homeless”, “special needs,” and “renters”. Although some of these terms have been used in the past — recall the image of the “welfare queen” — many of them persist in the dominant discourse and social imaginary around public housing.

While subject to these imposed meanings, residents are often also denied access to their own language(s) due to inadequate translation services. It is only through a common language that one can be heard and communicate, and it’s also through common language that one can create one’s own public and symbolic image. Limitations to language access can therefore become limitations to one’s representation of self.

A recent study led by the Urban Justice Center, the Community Development Project and the Committee Against Anti-Asian Violence surveyed 221 tenants of limited English-speaking ability at 14 NYCHA’s developments, and found that only 40% of tenants were connected with NYCHA to request services for spoken interpretation, and even fewer — 18% — for written translation . The research shows that most of the tenants rely on family and friends in order to communicate with the staff because NYCHA is not successfully communicating its language access services, and the language access staffing structure does not meet the needs of Asian tenants.

Thus, NYCHA seems to have to fight not just urban poverty, but also the stigma around its clients and the service it provides. It is important to acknowledge how the stigmatization can sometimes be entrenched within the institution itself; the language access issue is one of many examples in which that occurs. Other examples include social controlling policies, such as the permanent exclusion of tenants and their families for drug related crimes, or parts of the NYCHA tenant selection process itself.

At Urban Upbound, I had not only the experience of following the processes of designing, implementing and writing a research report on a professional level, but also of developing a critical and analytical outlook towards specific policies targeting urban issues such as housing, healthcare and public transportation. I was able to better understand of the role of nonprofits in assisting governmental institutions in delivering more holistic service to clients. Urban Upbound works closely with NYCHA in order to provide services such as college access to the youth, financial counseling, job placement and a federal credit union.

If I ever questioned our role as urban students, scholars, critics and researchers in making social change, now I can better understand how our work takes place within the structural relationships among a nonprofit, governmental institutions, and our own politics. I can securely say I feel more confident and ready to start my second and last year at the Murphy Institute.

Paula holds a Bachelor of Arts degree in Journalism from Universidade Fedral de Juiz de Fora, Brazil and is currently on track to receive a Master in Urban Studies with an emphasis on public policy from CUNY School of Professional Studies. Paula recently supported the “Healthy Aging in Far Rockaway” study with the organization Urban Upbound and is currently interning with the public policy department at the New York Academy of Medicine.