This article was originally featured at the Indypendent.

By Peter Rugh

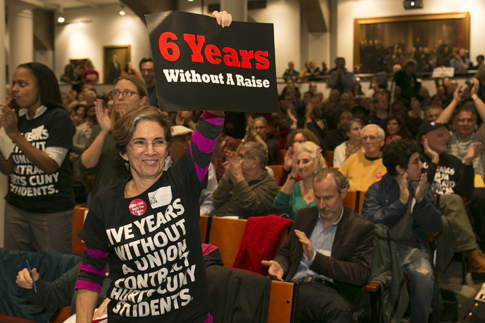

Hundreds of people swamped 42nd Street one day last November, forcing police to shut down a section of the busy thoroughfare. These weren’t tourists or Broadway ticketholders gone mad, but professors from the City University of New York (CUNY) and their supporters, 53 of whom were arrested for sitting down and blocking the doors of CUNY’s administrative headquarters.

“We took matters into our own hands,” said James Davis, a member of the English Department at Brooklyn College since 2003. “It might seem like an ironic statement given that the cops tied our hands behind our backs, but we were making a strong public statement in opposition to CUNY’s austerity regime.”

With 278,000 degree students enrolled in more than two dozen undergraduate and graduate schools, CUNY is the nation’s largest urban university system. Since it was founded in 1847 as the Free Academy of the City of New York with a mission to “serve the children of the whole people,” CUNY has served as a gateway to opportunity for working-class students. That continues to this day with 75 percent of undergrads being students of color and more than half coming from households earning less than $30,000 per year. Since the 1970s CUNY has been the largest granter of degrees to students of color in the United States.

When the financial crisis of 2007-08 hit, public sector institutions like CUNY were made to pay the price. The bulk of CUNY’s funding comes from the State of New York. According to recent testimony to the State Legislature by City Comptroller Scott Stringer, if aid to CUNY had grown at the same rate as the state’s operating budget over the past seven years, the system would have an additional $637 million on hand today.

Instead, students were hit with a five-year, 31 percent tuition increase in 2011 to help cover the funding shortfall and now CUNY is asking the legislature for permission to sock students with five more years of similar tuition increases. The higher tuition has been touted as a way to fund improvements at CUNY, but amid relentless budget cuts in Albany that has not been the case (see sidebar).

Austerity has also taken its toll on the members of the Professional Staff Congress (PSC), the unabashedly progressive union that carried out the November sit-in at CUNY’s central office. The union represents 27,000 full- and part-time faculty and professional staff. Its members have worked without a new contract for five years and haven’t had a raise in six. Despite a 23 percent rise in the cost of living in New York City, their salaries have remained where they stood in 2010. Now, exasperated by what it describes as the administration’s refusal to make a serious economic offer, the union has raised the specter of going on strike.

In October the PSC began circulating a petition among its members, asking them to pledge to vote “yes” on a strike authorization measure. Fearing a potential walkout, CUNY management filed a notice with the statewide Public Employment Relations Board in January, asking it to provide a mediator who would assist the parties with their negotiations. Frederick Schaffer, general counsel for CUNY, described a speedy resolution to the dispute as “critical for the stability of the workplace and morale of our faculty and staff.” However, the addition of a mediator to negotiations could extend the stalemate into next year as she or he gets up to speed with the details of the matter.

Confronting the Taylor Law

Complicating matters, New York State’s Taylor Law forbids public employees from striking. The last union to openly defy the Taylor Law was Transit Workers’ Union Local 100, whose members struck for three days in December 2005. The State retaliated by jailing Local 100 President Roger Toussaint for three days, fining the union $2.5 million and suspending automatic dues collection for more than two years before the union finally pledged not to strike again. PSC President Barbara Bowen acknowledges the risks associated with a strike would be high but warns that it might eventually be the PSC’s only option.

“We’ve done everything necessary to settle this without a strike,” Bowen told The Indypendent. “We’ve held rallies, press conferences, written letters, worked with legislators, conducted sit-ins. We’ve done everything we can think of and having found that those things have not fully succeeded, we’ve had to consider a strike. We’re well aware of the penalties and hope that we, that none of our members, have to face them. That’s not something we look forward to.”

The PSC’s current leadership emerged out of a wave of student and faculty struggles in the 1990s against budget cuts and other neoliberal reforms to CUNY favored by Republican Gov. George Pataki and Mayor Rudy Giuliani. In 2000, Bowen and a slate of reformers were swept into power, pledging to create an activist culture within the PSC that would catalyze the fight to win full funding for the university and keep it accessible and open to all New Yorkers. Sixteen years later the union continues to fight for that vision. Faced with a governor who by all appearances is indifferent to higher education, the PSC’s long-running contract campaign may be its most difficult battle to date.

Together with the union’s executive council, Bowen raised the possibility of strike authorization with PSC members at a union-wide meeting in November, and she expects a vote sometime in March, a time frame, Bowen said, that will allow for “serious conversations to take place and for real democratic consideration of what a strike will mean.”

Bowen also stressed that a strike authorization is not equivalent to a strike. It does, however, empower the union’s 27-member executive council to call for a walkout should it deem one necessary. PSC leadership will be “doing their best” to work with the Public Employment Relations Board-appointed mediator, Bowen said, but, she observed, “The real problem isn’t mediation. It’s money.”

It wasn’t until last fall’s sit-in at CUNY headquarters that the administration made an economic offer to PSC members: a 6 percent pay increase from 2010 to 2016 with no retroactive raises in four of those six years. Yet, as the union points out, the proposed raises are below the rate of inflation, amounting to a virtual pay cut.

“I have to make choices like whether to put food on my table and make rent versus whether to get new clothes for my kids and me,” said Brooklyn College Professor James Davis, a father of two.

CUNY teachers earn substantially less than their counterparts at comparable institutions. For instance, the average CUNY associate professor earns $91,500 a year, according to testimony Bowen delivered to the state legislature in January, whereas educators with the same title at the University of Connecticut earn $99,700 and $102,800 at the University of Delaware. Such a salary might seem ample but, in addition to the cost of living in New York, most professors accrue significant amounts of debt covering the costs of their undergraduate and postgraduate education.

“People’s spending habits have definitely become more constrained,” said Davis. “But beyond that it has become really hard for departments to hire top-quality teachers. Even if we can make a comparable salary to other institutions, candidates have to think seriously about coming here, given that the cost of living in this city is astronomical and climbing.”

Additionally, the PSC represents 10,000 part-time instructors who make poverty wages and have no job security, despite teaching 52 percent of classes at CUNY.

“We are not paid for class preparation or grading papers or email correspondence with students or writing students letters of recommendation or attending sometimes mandatory faculty seminars/meetings,” wrote Marcie Bianco, an adjunct in Hunter College’s English Department, for the news website Quartz in July. “If we teach at more than one school, we are limited to teach a total of three courses a semester, which, at my current rate, means I’d earn approximately $13,200 before taxes each semester.”

Note Bianco’s use of the past tense: her courses last fall were summarily cancelled due to a decline in enrollment.

To put things in perspective, CUNY Chancellor James Milliken received a base pay of $670,000 last year plus an $18,000 per month housing stipend and a free car and chauffeur. Milliken’s predecessor, Matthew Goldstein, was granted a lavish six-year, $2 million severance package by the CUNY Board of Trustees when he resigned in 2013 to become board chair at J.P. Morgan Funds for an estimated salary of at least $500,000 per year. Under Goldstein the university implemented the tuition hikes that have gone hand in hand with stagnant faculty wages.

Placing the Burden on Students

In 2011, the State Legislature passed what proponents, including Gov. Andrew Cuomo, termed a “rational tuition” plan for CUNY. The measure granted CUNY and New York’s state university system, SUNY, the ability to raise tuition by 31 percent over five years, which the CUNY Board of Trustees promptly elected to do.

The rational tuition legislation included a “maintenance of effort” commitment, stipulating that the state would maintain a steady level of funding that would encompass normal inflationary increases in operating costs. Yet CUNY suffered a $51 million dollar shortfall in 2015, despite the state’s multi-billion-dollar surplus (its largest since the 1940s) and in December Cuomo vetoed a maintenance of effort bill that passed the State Legislature with widespread bipartisan support. Now, CUNY management is asking the legislature to extend tuition increases for another five years.

For students of CUNY’s history, today’s austerity echoes back to 1976. New York City was in the midst of a fiscal crisis, the state took control of CUNY and, for the first time CUNY began charging tuition. Since then the university has increasingly been shifting its costs onto the backs of students, who are paying more for their education and getting less in return.

“When people are paying more they think that it will be invested in computers, classrooms, teaching salaries, student resources, but none of it is actually going to the maintenance of CUNY’s campuses” said Conor Tomas Reed, a doctoral student at the CUNY Graduate Center who works as a writing fellow at Kingsborough Community College in Brooklyn.

Today, the university draws about 45 percent of its budget from tuition while teachers and students complain of ballooning class sizes, fewer courses, under-staffing and damaged equipment, not to mention the difficulty departments face attracting educators without the ability to offer a competitive salary. The state’s Tuition Assistance Program has not kept up with the cost of attending CUNY, either. The maximum $5,135 students can receive falls almost $1,200 short of what it costs New York residents to attend one of CUNY’s four-year colleges and is not available to part-time students who often take fewer courses because they are carrying other responsibilities outside of school.

“There are a lot of CUNY students who are working minimum-wage, part-time service industry jobs and taking care of family needs because their families are at or below the poverty line,” said Reed, who worries the cost of the tuition hikes is having a disparate impact on low income and students of color at CUNY. Forty percent of CUNY students are the first generation immigrants.

“Our students very much understand there are economic choices here,” said Ben Shepard, an associate professor in New York City College of Technology’s Human Services Department who was arrested in the November sit-in. “They can participate in the black market economy: they can sell drugs. Or they can get an education and go to CUNY. CUNY gives them an opportunity to do something with their careers and their lives and yet it gets more expensive every year. This fight [over our contract] really is about the students because the sad fact is when faculty are underpaid the really great teachers are going to leave.”

The PSC is not the only group organizing for a possible strike. The Hunter College Graduate Student Union has begun an intensive one-on-one organizing effort among Hunter’s 5,300 graduate students with an eye toward carrying out a strike action in support of a tuition freeze full funding of CUNY, and a union contract with pay parity, job security, and workload flexibility for part-time faculty.

“Our approach has been to apply the basic tools of union organizing to student organizing,” said Erik Forman, President of the Hunter College Graduate Student Union. “By that I mean very systematically reaching out to students in different programs, identifying issues, building committees, and beginning a process of escalating action.”

Other groups that are mobilizing includes the University Student Senate which is organizing a March 6 march over the Brooklyn Bridge to oppose the new round of tuition increases and CUNY Struggle, a group of radical CUNY academics and their allies who will be holding a popular assembly at the Graduate Center on March 12.

Cuomo Drops a Bombshell

The most immediate challenge facing CUNY and its supporters is in Albany where state legislators are looking to conclude the annual state budget by the end of March.

After vetoing “maintenance of effort” legislation in December, Cuomo stunned many observers in January by proposing a whopping 30 percent cut in state support for CUNY’s 11 senior colleges, or $485 million that the City of New York would be invited to cover. It was Cuomo’s latest salvo in his long-running feud with New York Mayor Bill de Blasio who received strong support from the PSC during his long-shot bid for the city’s top spot in 2013.

Cuomo also proposed putting $240 million aside in this year’s budget to cover the costs of settling contracts with CUNY employees. But that figure would come out of the proposed $485 million cut.

Testifying recently to legislators in Albany, Chancellor Milliken described the consequences of nearly a half billion dollars reduction in state funding as being little short of catastrophic.

“Numerous colleges, depending on how you did this, would have to be closed,” Milliken said. “Or you’d take a 30-percent decrease across the entire system.” But Millken added he was not preparing for any decrease in CUNY’s budget and referred to the cut as a “shift in funding” in the belief that the city would pick up the tab if necessary.

CUNY’s faculty and students are caught in the middle of a political game of chicken, but If Cuomo’s $240 million contract settlement offer was an effort to divide-and-conquer them, it has so far failed. In January the union joined with several student and community groups to form the Community Alliance for a Free and Quality CUNY. Members of the coalition are actively engaged on a number of social justice fronts on and off campus — Black Lives Matter, defending the rights of undocumented students, opposing gentrification and the presence of military recruiters at CUNY schools — and have united to push back against the cutbacks the university faces. Building community support proved key to the success of the Chicago Teachers Union in its 2012 strike and PSC is deploying a similar strategy in New York. An outpouring of solidarity from the communities the faculty serve will strengthen the bottom-up pressure the union is seeking to put on Cuomo and CUNY management.

While Bowen argues money should be set aside for a new contract, she say it shouldn’t come at the expense of regular state funding. She estimates the real cost of providing new contracts for the faculty and professional staff and an additional 10,000 CUNY’s support staff who are not PSC members but have also been without a contract for six years, at $350 million. Albany is expected to approve this year’s budget by April 1, by which time a PSC’s executive council may or may not have been granted the authority to strike.

“We’re fighting for a vision of education for the people of New York City and New York State,” said Bowen. “That’s what’s at stake in our contract. It’s about whether the state and the city and CUNY management believe in high quality education for the people we teach or whether they do not. Investing in our contract is a direct investment in the quality of education at CUNY.”

Featured photo shows some of the 53 members of CUNY’s faculty union who were arrested Nov. 4 for blockading the entrance to the administration’s central offices. Photo Credit: Dave Sanders