By Kafui Attoh

Something exciting is happening in Poughkeepsie. In the last two years a group of local residents — under the name “Nobody Leaves Mid-Hudson” (NLMH) — have been organizing to fight for the rights of the city’s low-income residents. For those whose knowledge of Poughkeepsie begins and ends with “The French Connection,” Poughkeepsie is not unlike many postindustrial cities in upstate NY — defined by decades of capital flight, city center decline and entrenched poverty. In this context, the emergence of NLMH has been an important development.

More than anything, it has been important for what the group has already accomplished. Last year, NLMH spearheaded the passage of the state’s first municipal foreclosure bond law — an ordinance requiring owners of properties in foreclosure (mostly banks) to post a $10,000 bond to the city for upkeep. Poughkeepsie is only the seventh city in the country to pass such legislation. This year, NLMH has embarked on a new campaign aimed at fighting the Central Hudson Gas and Electric Company — the public utility monopoly that serves the Mid-Hudson region. As Central Hudson pushes for a rate hike and as local residents —already on the margins — consider the possibility of power shut-offs, NLMH has raised a set of important questions. What rights do people have to heat, electricity and a warm home? More to the point, what rights should they have?

This spring I sat down with some of the members of NLMH to ask them a set of “big picture” questions about how they understand their work — not only as organizers, or local residents, but as individuals seeking a more just society. Below you will find a transcript of that discussion. The hope of what follows, of course, is to offer the readers of this blog a glimpse of what I think is not only an incredibly dynamic and thoughtful group of organizers, but a group or organizers raising precisely the questions that matter for those of us interested in fighting for a more just city, a revived labor movement and the rights of low income people everywhere. Power to Poughkeepsie!

First, what is NLMH and how did NLMH start?

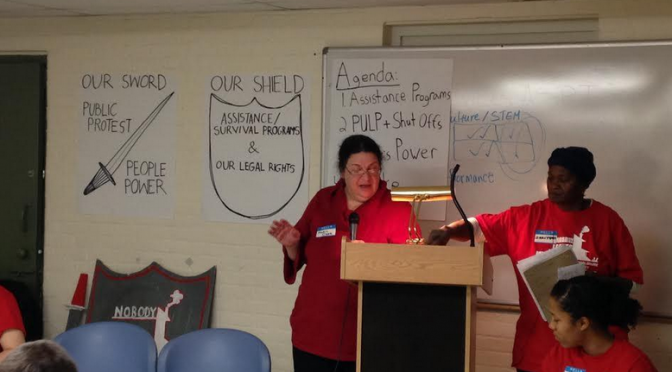

Nobody Leaves Mid-Hudson is a radical housing rights organization based in Poughkeepsie, New York. We spun off from Occupy Poughkeepsie in early 2012 after the occupation was evicted by local police. Our initial campaign was around foreclosure and eviction. We were very fortunate to link up with the Right to the City Alliance, a national alliance of over 50 racial, economic and environmental justice organizations, and similar organizations like City Life/Vida Urbana, a Boston-based social justice community organization. With their help we began using what they call a “radical organizing model” and the “sword and the shield.”

Radical organizing stresses organizing ideologically to identify the structural roots of everyday problems, making demands that challenge profit motives and market values, building the leadership of directly impacted people, and continually building a broader movement. The Sword and the Shield is a two-part strategy of public protest and legal defense that combines the power of collective action with legal rights and basic services to keep people involved while winning material gains. We adopted this model to fight foreclosure, but in 2014 we were hearing that a major source of housing insecurity and displacement was around unaffordable utilities. We made a commitment to adapt the radical organizing model for this campaign, and to retool our sword and shield. With a few leaders from the foreclosure campaign, a lot of research, and thousands of conversations in social service offices and at doors —we launched the People’s Power campaign.

Tell me about your membership. How many members do you have? Do they pay dues?

Our membership is primarily working class women of color living in the City of Poughkeepsie. We’re made up of mostly unemployed and underemployed workers who are forced to choose between which bills they will pay: medical care our housing, heating or eating. We have a loose membership of 30. We’ve just begun formalizing membership and a dues structure, and just last week started signing folks up and passing out membership cards. That’s a big step for us. One of our biggest challenges has been organizing in a small, post-industrial city, where there is a real lack of movement building infrastructure. It feels important to find ways to build that in places like Poughkeepsie, which have really become marginal within the U.S. political economy and demobilized politically.

Tell me about your first campaign. How does a foreclosure bond work? And why is it important?

We used a combination of legal pressure and direct action to defend individual homeowners against big banks. That was a complicated process, because foreclosure is a judicial process in New York State. We scored some important victories legally and through public protest, but our biggest accomplishment to date was the passage of a foreclosure bond. This was done in coalition with Community Voices Heard and with legal support from the Lawyers Committee for Civil Rights Under Law. A huge social consequence of the foreclosure crisis in Poughkeepsie is vacancy and blighting. The legislation forces banks to put down a $10,000 bond whenever they initiate a foreclosure and for each vacant property they own. The city can draw from the bond if the banks fail to maintain the properties themselves. For years banks have privatized the gains and socialized the pain of the foreclosure crisis, and this bond allows us to reverse that. The bond was passed unanimously in Poughkeepsie at the end of last year, making it the first legislation of its kind in New York. But we’re still pushing to begin implementation in earnest. We also contributed to the Right to the City Alliance’s successful campaign to push the Federal Housing Finance Agency to allow Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac to sell foreclosed homes back to residents instead of evicting them; to direct them to sell foreclosed properties to nonprofits instead of hedge funds; and to require Fannie and Freddie to pay into the Housing Trust Fund (for affordable housing for low-income people).

Tell me about your second campaign. How has it been different or similar from your previous one (organizationally, strategically)?

The People’s Power campaign is a struggle for affordable, sustainable, and just utilities. What we mean by that is first, prioritizing human needs over the profit motive in order to create a truly affordable situation for working class people. Second, we know that the consumption of gas and electric utilities is directly tied to the fate of environment. A successful movement to protect the environment has to come from the most impacted communities, especially working class communities of color. Therefore, struggles for affordability and sustainability have to be linked.

When we talk about a “just” world, we’re calling the system out. It is a racist system, in that Black and Brown folks are disproportionately having their power shut off and sinking into deep debt. It is a sexist system, in that the burden of survival is placed on the shoulders of women in the absence of a social safety net. And it is a system where there simply aren’t the jobs or income to pay the utility bills the way they are now. The fight for justice will require us to challenge that system head on.

Organizationally, we’re still taking on corporations directly like we did with foreclosure. We’re still using the sword and the shield, but we’re forced to rethink the model to fit a new context. We are working to enforce basic consumer protections in the Home Energy Fair Practices Act, helping folks apply to much needed low-income programs, and encouraging people to file complaints with the Public Service Commission in order to remedy Central Hudson’s consistent violation of the law. Additionally, we are using protest and publicity to put direct pressure on Central Hudson to negotiate with our members around debt and shutoffs, and to make critical changes like protecting children from shutoffs and lowering extremely regressive Basic Service Charges.

We also created what we call a Shutoff Free Zone. We will fight every shutoff of our members and ensure that the lights and heat stay on. We’re establishing the right to utilities in Poughkeepsie, and fighting like hell to realize that right. We see the Shutoff Free Zone as a particularly transformative part of our campaign.

We frame part of our fight around survival. If you’re a working class person who can’t afford your utility bill — as many Poughkeepsie residents are — you have to fight to survive. Many people have to fight on their own to get the assistance/survival programs they need to keep from getting shut off. But it also goes the other way — people need to survive so they can fight more for themselves, for others, for a better community and a better future.

Strategically, we are dealing with a target who has a history of regulation and even public ownership and at least on a paper a direct level of accountability to the public. Public utilities have really born witness to neoliberal deregulation. But there are still levers of public power, in our case the Public Service Commission. It opens up avenues for increasing public control, and it helps us imagine a world in which utilities are governed by and for the public, and not for capitalists.

Why should utilities be a right?

Almost everyone we talk to has a story about how a single utility bill can throw their life into disarray. Someone gets shut off, and their sick child can’t use a nebulizer. Someone else loses their Section 8 voucher because they couldn’t pay their utility bill, and they get evicted. Someone else has to move because no matter how much they cut down on their utility consumption, the bill is still 40% of their income.

What this points to, is that utilities are a necessary component of a right to housing. When they are not affordable, it is a health issue, it is a displacement issue, it is an insecurity issue. The Right to the City Alliance has included “fair” utilities in its Renters Bill of Rights as part of its Homes For All Campaign. That’s a critical addition, because utilities are part of a right to housing, and therefore a right to the city.

I think a more precise way of describing the way we think about utilities are that they are a human right and a public good, which ought to be subject to democratic, public control and guaranteed public access. As long as public goods like utilities are not subject to public, democratic control, we are not living in a democracy!

The right to utilities stands at the intersection of a number of other rights. It connects with issues of healthcare, issues of racial and gender inequality, and issues around labor and work. As a point of convergence for a variety of struggles, the fight for utilities justice presents an avenue to build a movement around broader set of social rights: the right the housing, to healthcare, to social justice, and to work. We think it can complement the incredible struggles that are happening within housing rights organizations, labor organizations, racial justice organizations, environmental organizations, etc.

Nobody Leaves’s goal is to find a way to wage that broader struggle in our own context, around an issue where we can win concrete victories and build real power. Because utilities really touch on so many struggles, because they are both shaped by both neoliberal deregulation as well as a rich history of state control, and because they provide a way for working class communities to address a growing ecological crisis, we think utility organizing is one strategic way to advance a broader movement, and to take capital head on.

As you know, the Murphy Institute Blog has a large following among members involved in the Labor Movement. What does NLMH have to say to such members? To what degree do labor struggles matter for what you do?

Samora Machel has that great quote about solidarity: it’s “not an act of charity but an act of unity between allies fighting on different terrains toward the same objectives.” That’s how we think about our work: advancing a broader working class movement on a specific, but complementary terrain.

It’s clear to us that we’re organizing workers, but doing it beyond the point of production — in fact, doing it at the point of reproduction. We have a lot to learn from the labor movement here. The most creative labor organizing in the last few years is coming to grips with the ways in which neoliberalism has reshaped work and the working class. We see examples like organizing low-wage service workers, organizing outside the traditional NLRB format, and organizing around racial justice and immigration reform as fights taking place within the workplace and outside of it. We take strategic lessons from the ways folks are building worker power by mobilizing community power, addressing the connections between work and home, and organizing those most impacted by neoliberalism — women, immigrants, and working class communities of color. We may be trying to organize around consumption, around the bills people pay, but it means we’re building working class power in the community.

Utilities are unaffordable because there aren’t jobs and income in our area. For that reason we often say, “No jobs? No income? — No shutoffs!” That’s a really radical proposition. The more we can link up with organized labor, and build a movement that fuses struggles for better jobs with a struggle for housing rights, the more we’re organizing “whole workers” in a movement that speaks to their needs.

Of course that needs to be ideological. If we fight these fights without the “unity” that Machel refers to, without forming real links around a real vision for power, then I think we’ll remain only rhetorically linked.

On a more local note, we’ve struggled to build these kinds of coalitions in the Hudson Valley, and we’re really looking for allies to help us move in that critical direction. If we could have “a union at work, and a union at home,” I think we could see a significant leap in working people’s power here in Poughkeepsie.

We understand concerns of utility workers — they see consumer power as something that will hurt their interests as workers. It’s a failure of our movement, and a testament to the power of capital, that we can’t create a shared identity as “whole workers” that unites and fights against corporations. We need to keep talking about how our interests are linked. Utility workers are consumers too. Central Hudson’s parent company, Fortis, cares little for the fate of the region and the people who live there, and is perfectly willing to outsource work and bust up the union. Community support can bolster workplace action, and can create a common front against Central Hudson. A stronger labor-community alliance can help us withstand the assault on working conditions in the Hudson Valley and other similar areas. Such an alliance, however, requires a politics of struggle. We think that folks at the Murphy Institute have done, and can continue to do, a critical job of pushing the labor movement toward this politic.

How does this campaign fit into your larger vision for the city, for a just society, or at least for a different Poughkeepsie?

Our work is definitely small. Right now, we’re a part of a Left that is asking questions about how all this work adds up. I don’t think there are definitive answers yet. But it’s clear to see that corporate power is growing, that exploitation is felt in both workplaces and communities, especially among working class women, people of color, and immigrants, and that the regulatory state has been gutted. The institutions of struggle that have helped build powerful movements are also in decline. Trade unions in particular, but many workers institutions — hell, even the idea of workers’ institutions — have really been beaten down. In a small way, in our own context, we’re trying to rebuild institutions.

Historically, these institutions built our capacity for struggle; they trained leaders as both thinkers and fighters. They helped win real gains, and in the process, acted like schools for movement building and social change. We need them today, and we need a strategy to grow and unite these institutions. Ella Baker called it spadework. We see every shut off we prevent, every movement song that we learn, and every right we claim as a part of that spadework.

As you’ve mentioned, you are affiliated with the Right to the City Alliance, how would you say your work fits within, or builds upon the mission of that organization. What does a right to the city framework add to your work?

Through the research we’re doing, thanks in part to the folks at the Sociological Initiatives Foundation, we’re deepening our analysis of utilities, and beginning to propose some much needed policy changes. All that is a part of Right to the City’s Homes For All campaign, which is uniting renters and homeowners in the struggle for affordable housing. “Fair utilities” is a key part of their renters rights, but because so few organizations are doing base building work around utilities, we’re working really hard (even as a very small organization) to think through what “fair utilities” really means, and what type of policy can make that real.

Where is NLMH going? Beyond the immediate campaign, what are your hopes for the organization?

This People’s Power campaign is a new one for us. We’re always trying to punch above our weight and do something transformative, but the reality is we need to dig in and build a strong organization, win more victories, and build our capacity. We’re going to really need support from within Poughkeepsie and allies beyond it to hit the streets and do the necessary thinking and learning work. We want to do a better job reaching monolingual Spanish speakers and addressing the intense utility injustice the recent immigrants face. We want to build coalitions with environmental groups, labor groups, and other groups statewide. And we want new members to help us put together a report on policies for a just utility system.

If we can do that, and build something deep, we think we can help spread the “radical organizing” model, and retool the “sword and the shield” and in some small way, do that really critical spadework in a small, hard-hit city like Poughkeepsie.

How do you hope to sustain momentum (gratuitous snacks, naps….)?

Coffee and solidarity. Oh, and donations.

Fin.

I appreciate the sense of community and labor partnership being strengthened by the awareness of our history and battles won. With an intentional eye to labor and community struggles we can see that we are not free until we all are free. And yes, we are “whole workers” with “whole lives”. Good to see organizing around this frame. Indeed, something exciting is happening in Poughkeepsie!