By Zenzile Greene

On the heels of the Spike Lee Retrospective being shown at BAM Cinematek through July 11th, I would like to present a piece I wrote up on assignment for my “Culture Through Film” class taken this past fall at the School of Professional studies. The course, taught by Professor Kelley Kawano, was developed brilliantly not only for the purpose of traditional Film History survey, but also towards the goal of turning a critical lens on the pervasive and myriad ways in which culture influences film and vice versa.

Over the course of the fall semester, we viewed and deconstructed a range of films from the Silent Era to the Hollywood Studio Era, to the groundbreaking independent films made by such pioneers as Irving Penn and Spike Lee. For several of our weekly assignments, we were asked to take one scene from a movie and analyze its use of one in a list of primary technical film elements, including editing, sound effects and direction.

For inspiration, I drew on the use of symbolism in Spike Lee’s “Do The Right Thing” from a paper I wrote in the class “Mass Media in Black America” taught by Professor Arthur Lewin at Baruch in 2010. I was very excited to write up a brief analysis of the symbolic use of editing in one particular scene of this, one of my favorite films in Lee’s “Brooklyn Trilogy” series.

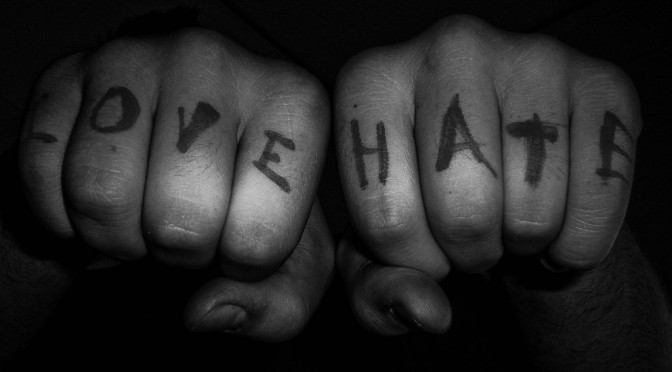

In “DTRT,” the ways in which the film’s main character Mookie negotiates the terms of relationship between himself, his employer Sal and his sons and the neighbors in this fictional version of Bed-Stuy Brooklyn are reflective of the ways in which people of color have always balanced the “color line.” This is a term coined by W.E.B. DuBois in the 1800s in his book The Souls of Black Folks as a way to illustrate the struggles of Black Americans to see themselves outside of a standard of value projected on white dominant culture. In his discussion of “double consciousness,” DuBois also speaks to the struggle of “twoness” and internal division experienced by Blacks, particularly with regard to work. In “DTRT” Lee uses the character of Mookie to demonstrate the complexities of this struggle.

Essentially, the themes of tension around issues of race, class and social structure that are at the crux of “Do The Right Thing” rest on the inevitable explosion that occurs as a result of Mookie’s inability to manage the highly problematic prejudgments made toward one another by his employer Sal and his sons and his friend, Buggin’ Out. Both Sal and Buggin’ Out represent frustrations of those on both sides of the issue of the responsibility of business owners and or ushers of gentrification to the residents whom they serve. The degree to which that service places white owners in a position of power shows how this may possibly replicate oppression reflective of the historical persecution of Blacks by Whites during America’s Slave era.

The scene in which Buggin’ Out first notices that there are no photographs of Blacks in Sal’s Pizzeria is effectively edited to establish for the viewer the moment where any hidden or previously dormant tensions with regard to fair treatment and an imbalanced power structure will no longer be tolerated or passively accepted.

As in most of the film, Lee edits a range of traditionally-used shots such as wide angle, framing, eye line match and dolly shots in ways never seen before to depict a theatrical tableau of colorful characters set against elaborate and politically charged neighborhood murals in order to stitch together a series of scenes which lead elegantly and turbulently to a fiery climax. In the scene I have chosen to analyze, Lee makes an editing choice that continuously impresses me each time I see it. He pushes the camera through the screen of the door to Sal’s Pizzeria seamlessly in order to match the reaction by Buggin’ Out to Sal’s insistence that he leave the store on the grounds that he is being disrespectful. There is an unspoken sense of underlying indictments being made on both sides, and in this way we can see them played out literally side by side in one continuous uncut take. We see the interior of Sal’s Pizzeria from which Sal leads Buggin’ Out to the sidewalk to exchange dialogue and then are brought back again to Mookie and Sal, who exchange dialogue inside the pizzeria.

Two very specific messages are communicated to the viewer in this scene. Before Mookie leaves Buggin’ Out on the sidewalk with the agreement that he stay away for a week before the disagreement can be reconciled, Buggin’ Out tells Mookie to “Stay Black.” When Mookie returns to the interior of Sal’s pizzeria, Sal continues to complain to Mookie about Buggin’ Out to which Mookie replies that it is a “free country.” Sal responds, “There’s no free here. I’m the boss.” The composition and framing of this long shot serve to juxtapose these two ideas in a discomforting and familiar way. It places the idea of freedom, usually evoked by corporations as a marketing tool or political strategists as campaigning propaganda, against the reality of white male patriarchy and a racially-biased social system. The conclusion of this scene sets the stage for a series of events to flow from these two realities in a way that ultimately climaxes in violence.

Symbolically, Lee’s use of the screen door push in shot does as much to keep the viewer engaged as it does to keep the action between these dynamic characters fluid and uninterrupted. Lee could have easily cut from Sal and Mookie inside the pizzeria to Sal and Buggin’ Out out on the sidewalk. The average filmgoer is rarely even aware of the traditional cut away reaction shot because it occurs so regularly in film. But Lee’s choice of technique allows the viewer a sense of continuity in this scene which is not only intimate and inclusive but also polarizing and immediate in the context of what we can sense building in the raw reactive energy of the characters involved. The viewer has the sense of someone looking on from inside the pizzeria. In effect, they are witnessing both sides of an argument whose broader implications are still largely ignored and unexamined in mainstream film.

Zenzile Greene is a poet, writer and photographer with a degree in Media and Social Issues from the CUNY GC Baccalaureate Program. She and her husband Francis Daniel live in Harlem, New York.