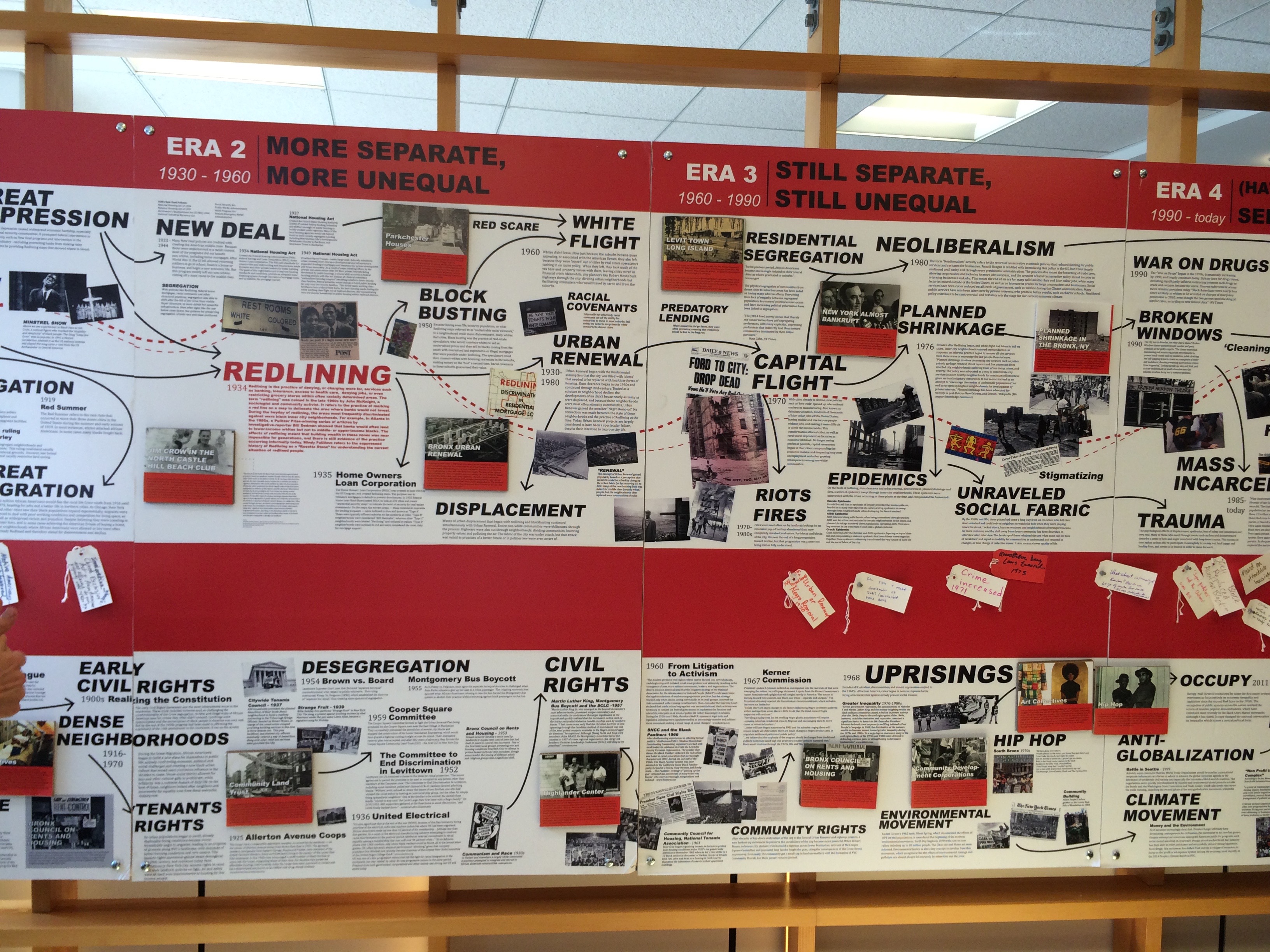

In recent years, “gentrification” has infiltrated the everyday speech of urban residents struggling to stay in their communities in the face of rising rents. But gentrification is only one piece of a much longer history of displacement and policy-produced poverty in American cities. This history runs from slavery through Jim Crow, redlining, racial covenants, blockbusting, urban renewal, capital flights, planned shrinkage, the war on drugs, mass incarceration and serial displacement, and weaves a painful narrative of structural racism whose practices and consequences remain alive today.

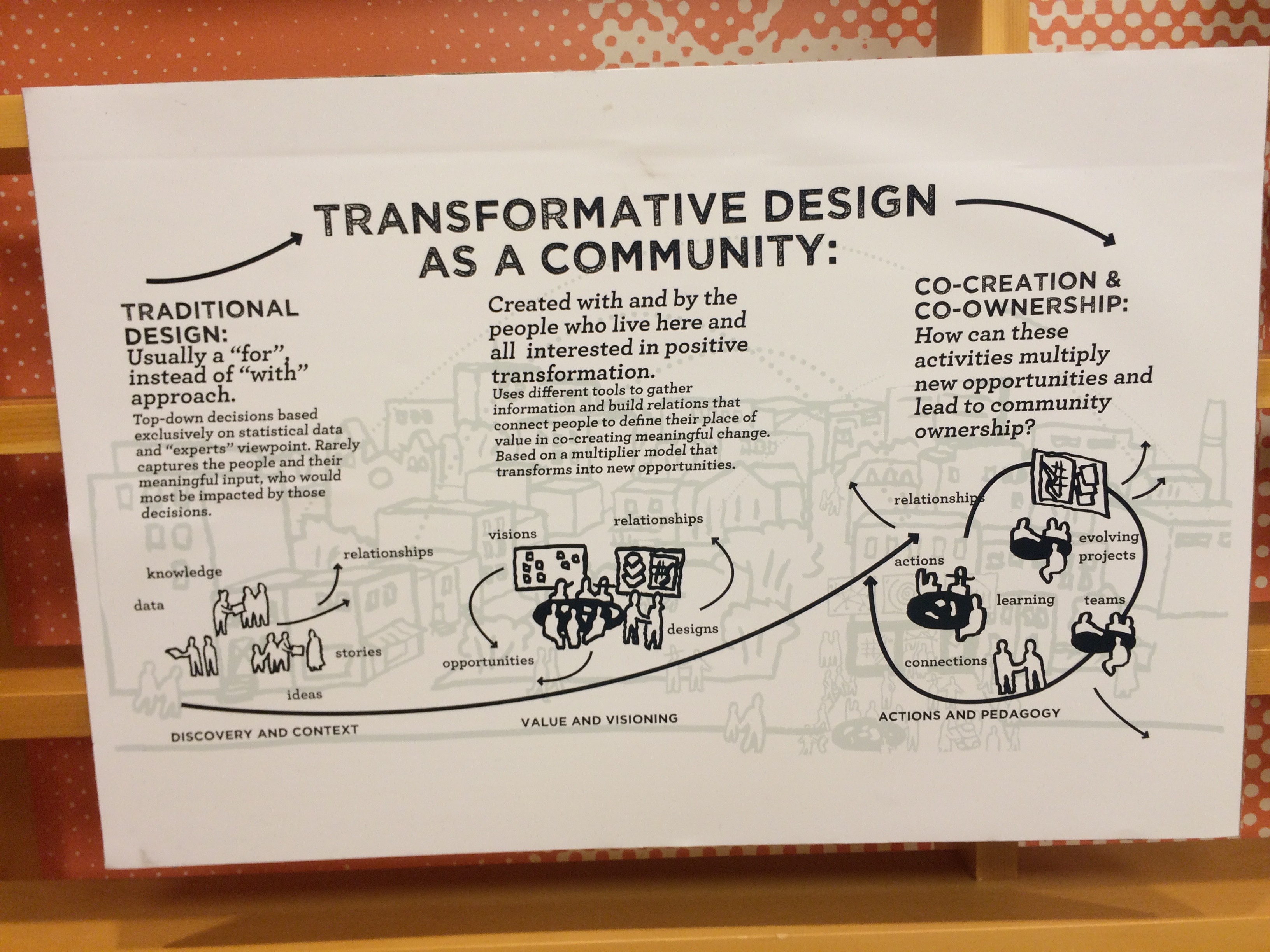

In “Undesign the Redline,” designing the WE — a “social impact design studio” — illustrates this history in illuminating and sometimes painful detail. Currently on exhibit at the New York City offices of Enterprise Community Partners, this exhibit includes photography, maps, timelines and tools for community engagement, and puts present struggles for racial equality in historical perspective. Using housing policy as an anchor, Undesign the Redline makes it clear that segregation and persistent poverty are the natural outgrowth of a system that has explicitly divided people based on race.

The “redline” of the exhibit’s title refers to a particularly pernicious practice that started with the passing of the National Housing Act in 1934. This Act established the Federal Housing Authority (FHA) in order to regulate the mortgage market and make home ownership more accessible by insuring federal home loans. It also resulted in the production of a set of maps that coded neighborhoods using a classification system that banks then used to determine eligibility for loans.

This system was explicitly racist: neighborhoods that were “green” were comprised mainly of white people, while “red” neighborhoods were any with black residents. Housing in red neighborhoods was effectively condemned — it became near-impossible to get a mortgage, which caused values to plummet and led residents of those neighborhoods toward enduring poverty. While redlining was officially outlawed in 1968, we still live with its effects today.

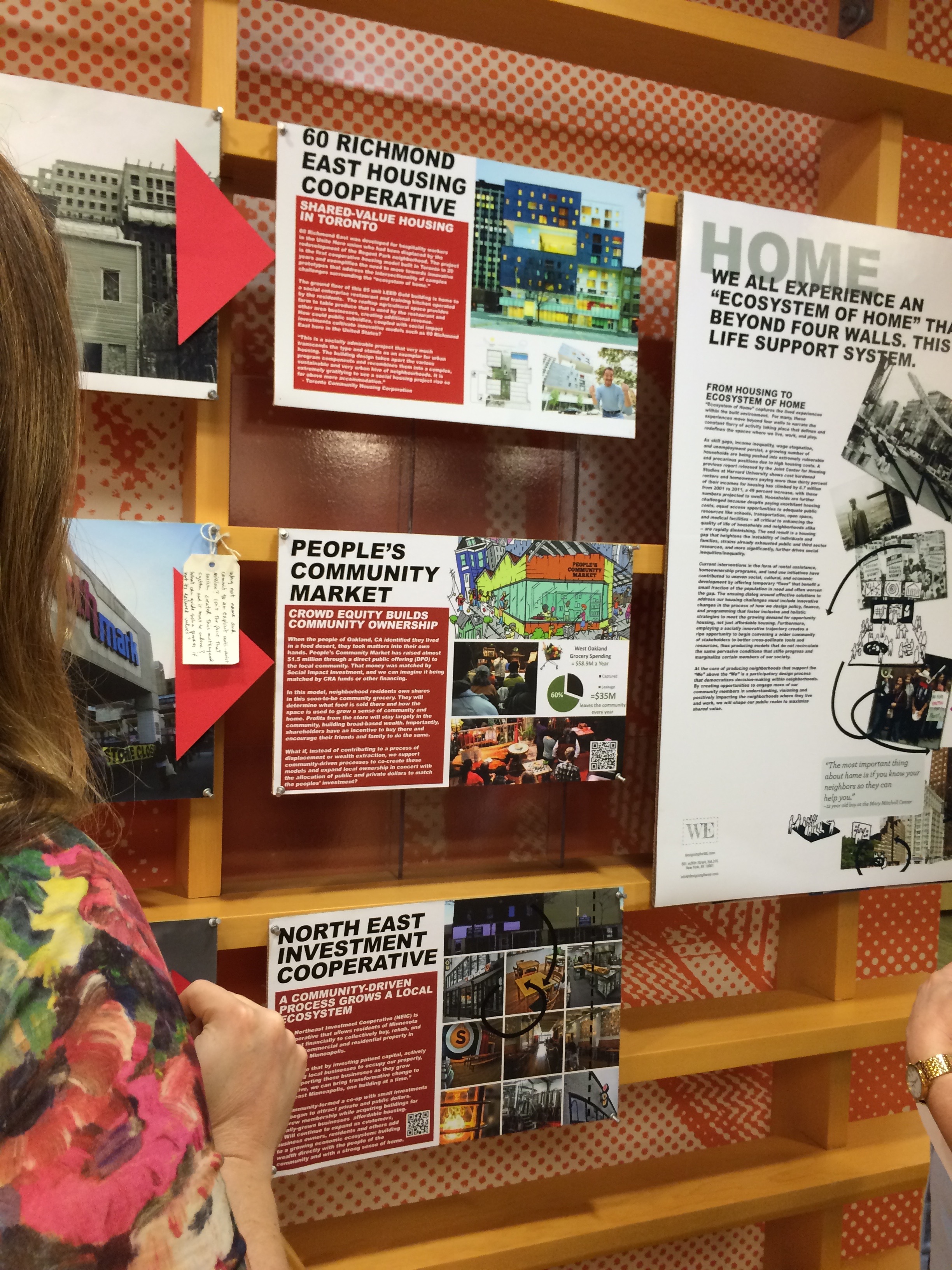

Using blown up images of old HOLC lending maps, Undesign the Redline shows how neighborhoods that were “redlined” in the 1930s are many of those that are today going through a process of gentrification. While the communities are now receiving investment, the benefits of that investment are largely accruing to new residents — not those who lived with the economic depression that resulted from redlining and the policies that followed. As Braden Crooks, co-founder of Designing the WE explains: “today, the tide’s rising, but it’s just washing people’s boats away.”

Although dispiriting in the policy history it tells, Undesign the Redline ultimately begs questions of participation and imagination. Its timeline of policy missteps sits atop another, more hopeful timeline: one of social resistance and community organization, including the cooperative movement, civil rights, the environmental movement, the anti-globalization movement, Occupy, #BLM and more.

Citing the limitations of the Community Reinvestment Act of 1977, the federal corrective that was designed to undo the consequences of redlining’s disinvestment, Undesign the Redline begs its viewers to invent new alternatives. How can we move toward a model of community investment that builds towards an “ecosystem of home” — one with an eye towards community wealth building and ownership?